Hardware founders are a different breed

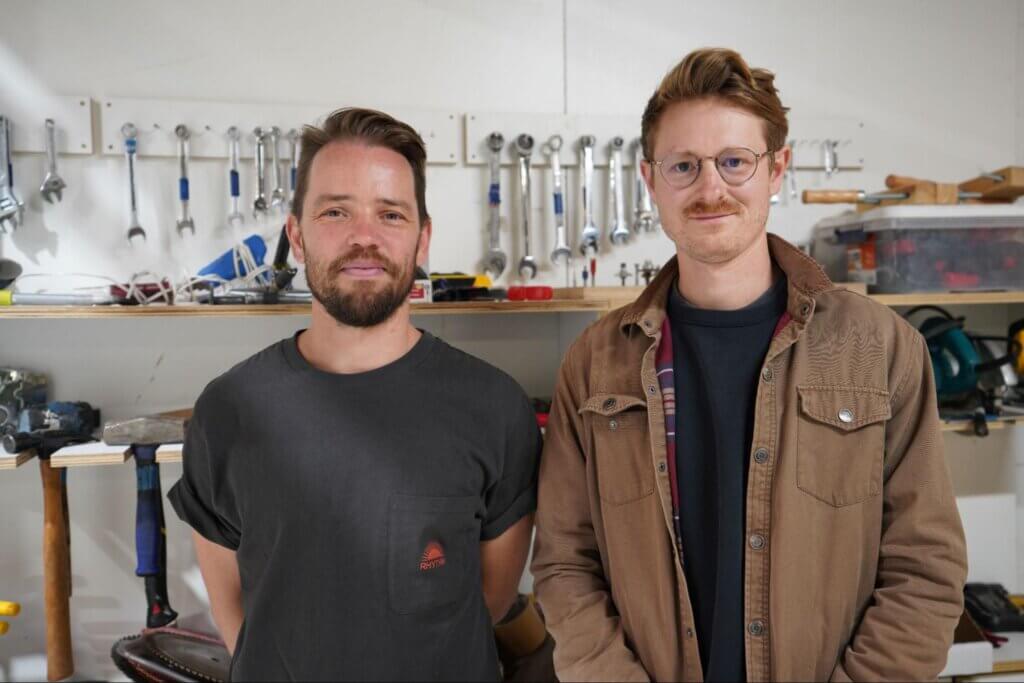

This is Part 1 of a three-part series on hardware as a distinct class of company. In this installment, we look at what draws founders to hardware and how building physical products shapes the people who choose to do it. (Pictured above are Pila founder Cole Ashman at right and Pila’s head of engineering Niko Dunkel in their workshop.)

Anyone building a hardware startup will tell you the same thing: You don’t end up here by accident.

If you’re a founder, there are far easier ways to make money, make an impact, or build a career, and most of them involve software. In an age where AI can compress software teams to almost nothing, that just makes software businesses even easier to build. You can easily “ship” your product (I’ve always found it funny that software teams use this word that comes from shipping actual goods, but I digress) and iterate while customers are using it. It’s what puts the “soft” in “software” businesses.

But that’s not how hardware works. You can’t prompt your way to a product that lives in someone’s home, keeps them safe, or becomes part of their daily routine. You have to build something people physically coexist with, ideally for years and years. Once a plastic or metal product leaves the factory, it doesn’t disappear when you ship a new version. Best case, it’s repaired, resold, or recycled. Worst case, it ends up in a landfill and outlives the company that made it.

As a hardware founder, you need to hold that reality alongside everything else that goes into building a company. You’re not just inventing something new — you’re committing to scaling it responsibly, often to millions of units, if you want to stick around. That’s why companies like Apple are ultimately operational machines, not just product studios. Hardware pushes founders into a different relationship with consequence, time, and scale than other venture paths ever require.

As hardware becomes sexy again and a new wave of young founders (and investors) aspire to make their dent in the world with physical products, we thought it’d be helpful to put in writing what sets hardware founders apart, what sets their companies apart, and how someone should think about investing in hardware startups. It’s not for everyone, but for those who are willing to put in the time, there’s no better company to build than one making hardware.

It all starts with the hardware founder’s appetite for risk.

Hardware founders take bigger risks

Founder and machinist Mark Schmick invested in tooling before launching his business, Flying Chair.

Starting any company is risky, but not all risks are created equal. When you have to invest in tooling to even start your business, you’re taking on a lot of risk (in time, space, money) that may or may not pay off. In hardware, that’s standard.

Software companies primarily wrestle with scaling teams, culture, and distribution. Hardware founders take on those same challenges plus manufacturing, supply chains, compliance, and physical failure modes that magnify with scale. If you’re building a consumer or industry-specific product, you can’t rely on grants or academia to absorb early risk the way deep science startups often can. You’re spending real money long before you have proof it will work — like James Dyson burning through thousands of prototypes or Tony Fadell preselling a promise before Nest existed at scale.

This is why building a hardware company can feel like 4D chess. Decisions you make early (components, suppliers, tooling) will come back years later with real financial consequences. It wasn’t a surprise that Tesla’s Model 3 production ramp struggled: Doing everything in-house and automating manufacturing prematurely rarely goes well. Most founders avoid this path because the risk isn’t abstract. It punches you right in the face the moment you start making your product at volume.

Hardware founders know this and choose the hard path anyway. Not because it’s easy, but because the problem they’re obsessed with demands a physical solution. Even though modern components, SOMs, and integrated electronics have lowered the barrier to entry, that’s just the first 20% (at most) of the business. The remaining 80% — the scaling and operations requirements that are murky at best in the early days of a startup — is where hardware companies are made or broken.

Hardware founders bootstrap by default

Rocky Talkie bootstrapped to over 30 team members and 7 figures in annual recurring revenue.

Most hardware companies start bootstrapped, whether founders want them to or not.

Raising capital before a working prototype is rare. Raising before revenue is harder still, especially when you’re being compared to software startups posting triple-digit growth in weeks. As a result, hardware founders self-fund, lean on friends and family, or find creative ways to generate early cash, like consulting, accessories, services, or adjacent products. Many companies (including Spanx, GoPro, and Ring) bootstrapped, not out of ideology but necessity.

The danger with bootstrapping isn’t finding money (though that will certainly keep you up at night) — it’s the timing of the money and the risk that short-term revenue paths will distract from the core business. Consulting, grants, or side products can quietly become the ends rather than the means if founders aren’t disciplined. Even well-capitalized founders self-funding their startup will feel pressure by month six if R&D is still consuming the rest of the company’s cash.

What distinguishes hardware founders is their tolerance for this phase. They operate under different business physics: slower feedback loops, higher stakes, and fewer chances to reset. That environment breeds strong financial controls, exceptional prioritization, and early attention to monetization, not as a growth hack, but to survive.

Hardware teaches resilience

Hardware companies require patience, iteration, and grit. Building Lodge wasn’t easy.

Hardware is less forgiving than software in every dimension.

Software breaks quietly and gets patched. Hardware breaks loudly, often with recalls, warranty claims, or reputational damage. No two physical products are truly identical. Tool wear, environmental conditions, and component variability mean every unit in the field is slightly different. Early hardware teams routinely scrap 10–20% of finished goods, a concept that simply doesn’t exist in software.

Factories miss deadlines. Components go out of stock. Regulations slow launches. Inventory locks up cash. If you build hardware long enough, you’ll face a moment where survival feels uncertain. Tesla called it production hell for a reason. Peloton learned how quickly demand and logistics can fall out of sync. Fitbit spent years navigating margin pressure and platform shifts.

Hardware founders embrace this reality and build their companies with it in mind. If they truly believe in what they’re building and the impact it can have, then these rough spots are just part of the journey. And getting through them prepares founders for their next product, and sharpens their abilities as entrepreneurs.

Hardware forces global thinking early

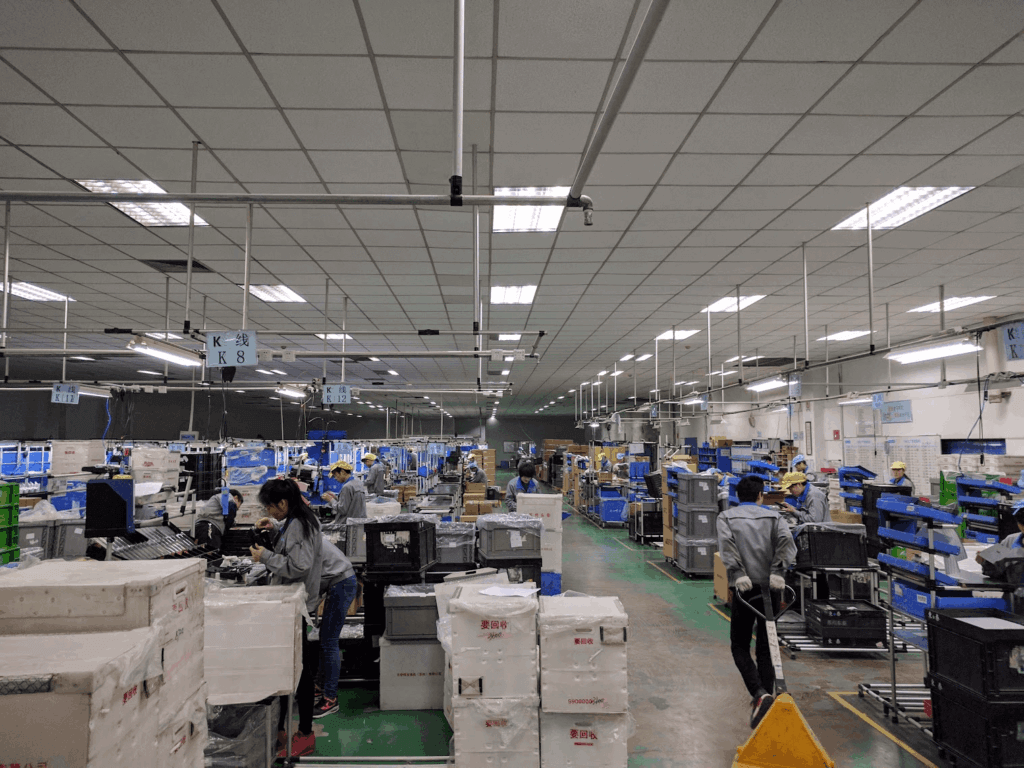

Every hardware founder relies on a global supply chain.

You can’t build a hardware company without a global supply chain. From day 1, you need to think about the fastest, most cost-effective way to get parts made, components sourced, and your entire product assembled. The very existence of your company depends on choosing the right partners and manufacturing strategy.

While software companies can stay local for years, hardware teams deal with international suppliers, overseas factories, shipping constraints, currency risk, and geopolitics from the start. A single component choice can introduce six-month lead times or single-source risk. Manufacturing problems can’t be solved asynchronously from a laptop.

The best companies turn this constraint into advantage. DJI leveraged Shenzhen’s ecosystem and global distribution network to out-iterate competitors. Apple’s enduring strength lies in its global operational mastery. Hardware founders learn early that scale is physical and interconnected; you can’t local-optimize your way through a global system.

This worldview tends to persist. Even when hardware founders later build software or platforms, they carry a deeper respect for systems, dependencies, and real-world constraints.

Hardware is a long game

It took Boston Dynamics over 10 years to develop their Atlas humanoid.

Hardware rewards patience because it simply takes longer to build real things than digital ones. When you’re constrained by physics and the timescale of fabrication, figuring out the optimal solution is going to take longer than you want. Why? Because you have to actually build a prototype and test it in the field with real users. Only then can you fully understand what’s working and what’s not. Then it’s back to work on the next iteration.

Development, certification, manufacturing, and distribution take time. There are no shortcuts when making novel physical things. Boston Dynamics spent decades before commercialization made sense. SpaceX failed publicly for years before reshaping launch economics. Eight Sleep didn’t win with version one of their mattress cover. They won by sticking with the problem.

This timeline reshapes how founders measure progress. Years spent improving reliability or manufacturability may look stagnant from the outside, but internally, they’re often existential. Hardware founders learn to think in arcs, not sprints, and to operate without constant validation. That’s why when they succeed, the results are often lasting.

Why this matters

The world needs more IRL innovation. Hardware founders are putting in the work.

Over the last 30+ years, the tech and startup ecosystem has optimized for what scales the fastest with the least amount of friction. This has created a bias for software and products that are more iterative than transformative. It’s produced enormous financial value and made peddlers of other intangibles (like bankers) very happy. But it’s also discouraged the brightest and most ambitious founders from working on physical problems like energy, manufacturing, healthcare, infrastructure. These domains are slower, harder, and less legible to software-native metrics. But they’re essential to the abundant future we all dream about.

Hardware founders run toward these problems — not away from them and toward the quickest buck. They build things people touch, depend on, and that transcend screens and the safe digital cocoon of the internet. That physicality comes with responsibility. The consequences are real, which is why the work is so important.

Not everyone wants to spend their life in feeds and dashboards. Many want better tools and better infrastructure in the physical world. Hardware founders choose to work there and that choice shapes both the companies they build and the leaders they become.

In Part 2, we’ll look at how these traits show up in hardware companies themselves and how they’re different from their digital counterparts.

informal is a freelance collective for the most talented independent professionals in hardware and hardtech. Whether you’re looking for a single contractor, a full-time employee, or an entire team of professionals to work on everything from product development to go-to-market, informal has the perfect collection of people for the job.