Manage product development risks using sling-and-stone engineering

We’re all familiar with the tale of David and Goliath. David uses courage and resourcefulness to take down Goliath with a simple sling and stone.

Behold the much nerdier saga of how I developed a new framework for prioritization after wasting time creating a complex engineering test rig (nicknamed Goliath), only to have it rendered obsolete by a literal stone.

The project: A grinder for entry-level coffee geeks

The team was in the early, early stages of developing this coffee grinder. Our goal was to build something that stands out in a crowded market, with the constraint of a sharp price target.

The concept:

- A vertically oriented coffee grinder

- that grinds as consistently as an expensive conical burr grinder

- without a curved chute, so it can’t get clogged

- and hits a super sharp price point for entry-level coffee makers who want to grind their own beans

An idea! What if we used ceramic burrs instead of stainless steel?

Ceramic burrs are way cheaper than machined steel conical burrs. Salt and pepper grinders use them and they work fine. This could be the big “unlock” to allow us to carve out some space in a crowded field.

But we had a lot of questions:

- We know ceramic burrs aren’t made with the same dimensional precision as steel. Can we get a good grind quality out of them? Best-cup-of-coffee-ever grind quality? SCAA-approved grind quality?

- Ceramic burrs aren’t as sharp as steel burrs. How does that change grind speed and grind consistency?

- What else could go wrong? We didn’t know.

The Goliath test

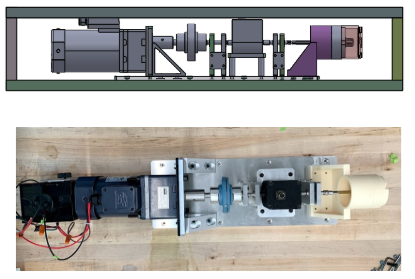

I got to work designing and building a test rig to start answering these questions.

- Machined stainless steel mounting plates

- Ultra powerful motor and speed controller

- Clutch to protect the motor

- 3D-printed housing for holding beans and mounting different burrs

- In-line torque gauge

Badass. (But it took me a few weeks.)

We started using the rig, now lovingly called Goliath, to test whether or not ceramic burrs were viable. We ran:

- Torque testing with ceramic burrs and steel burrs to determine what size motor would be required in the finished product.

- Coffee grind size distribution testing, which compared results to SCAA standards and control samples. Based on results, we adjusted how the burrs are held in the housing to optimize grind consistency.

- Coffee flow rate testing, which showed that the ceramic burrs would be too slow. This led us to design plastic parts to act like an auger to increase bean flow rate.

- Another round of torque and sieve testing with the new auger.

Things were looking promising! And there was a lot of ground coffee in our office.

A few more weeks had passed.

DFMEA

At this point, we felt confident in the integrity of the design. We were ready to kick off the DFMEA (design failure modes and effects analysis).

FMEA is a risk-management tool that evaluates how a process, design, or component might fail, and the consequences of that failure. It‘s a formal framework that provokes cross-functional teams to brainstorm risks. DFMEA is focused on the risk of different design elements. Typically, there’s a separate PFMEA to evaluate process.

The goal is to outline in detail:

- Failure modes: Specific ways a function might fail (a part breaks, a sensor fails)

- Effects: The consequences of those failures (system shutdown, safety hazard)

- Priority: Proactively identify and rank risks by their impact on safety and quality

FMEA has a rich history and has been used across industries as a technique to mitigate risk. It was developed by the U.S. military in the 1940s as a reliability technique to reduce failures in weapons and equipment. In the 50s and 60s, it was adopted by the aerospace industry, notably by NASA for the Apollo space program to manage high-stakes safety risks. In the 1970s, the automotive industry adopted FMEA to improve vehicle reliability and handle regulatory scrutiny. In 1982, the Automotive Industry Action Group (AIAG) published the first official FMEA reference manual, and it has since expanded to sectors such as healthcare, nuclear, and manufacturing.

A standard FMEA Analysis has four main components:

- Severity: How serious the impact of the failure is

- Occurrence: How likely it is for the failure to happen

- Detection: How likely the failure will be detected before it reaches the end user

- Risk Priority Number (RPN): A calculated score based on severity, occurrence, and detection to prioritize which failures need immediate attention.

We began the thorough process with multiple half-day meetings with a handful of engineers and product team members brainstorming risks. It’s an incredible way to prioritize work on a complex project. It’s also quite arduous.

In our FMEA spreadsheet, one row simply read, “Rock in the burrs.”

Our internal quality department is keenly aware that, occasionally, bags of coffee contain rocks that are roughly the same size as a coffee bean. It’s a natural product made globally, and not so uncommon for a rock to get mixed in with the pre-processed coffee. During the cleaning process, the mesh filters don’t sort out rocks that are exactly the same size as a coffee bean.

As an engineer who had worked on many coffee products, I too knew this fun fact.

The David test

On the flip side, the David test took about 21 seconds:

- 10 minutes to take the elevator downstairs and find a stone the size of a coffee bean.

- 10 seconds to put it in a pepper grinder and twist

- 1 second to see the pieces of ceramic that had chipped off the burr

One little stone told me definitively, “We can’t use ceramic burrs in this product.”

One little stone rendered my Goliath test rig (mostly) useless.

One little stone that, if I had found two months earlier, would’ve saved me a whole lot of time and effort.

Learnings

I never waited for the formal FMEA again.

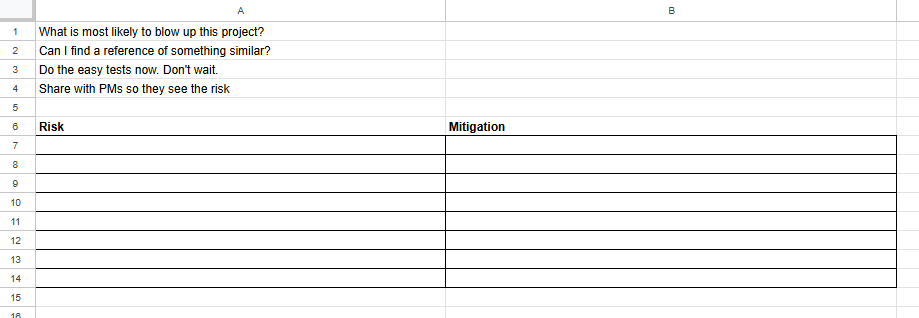

Now, at the very start of each project, I create a simple sling-and-stone doc with risks and mitigation plans. At the top of the doc I have a few prompts as reminders:

The simplicity is key. I can easily open this doc and jot down a thought as I have it, like “rock in the burrs.” And if the mitigation step is going to take a few minutes to resolve, I do it that day.

You wouldn’t believe how much time it’s saved me. It’s an example of the difference between operating as a PE versus a Senior PE. When you learn to answer big questions as simply as possible, you can take on more projects, more complex projects, and move faster. I even kept this up as an engineering manager and have lists going for each project under my oversight. It helps me keep the team focused and working efficiently.

And when it’s time for that formal FMEA, you’re ready. No prep needed. “Let’s schedule it for tomorrow morning.”

The sling-and-stone method

- Write risks early, continuously.

- Hunt for fast disproof tests and run them ASAP.

- Save the big rig for when the cheap test can’t answer it.

Moral

David engineers outperform Goliath engineers because they solve the right problems at the right time.

About the Author:

Dan Juda is a Montclair, NJ based mechanical engineer and Fractional C Suite member of informal with 13 years of experience leading hardgoods product

development at OXO, Hydroflask and Osprey (Helen of Troy). Shipped 100+ successful consumer products across kitchen, housewares, cleaning, and juvenile categories.

informal is a freelance collective for the most talented independent professionals in hardware and hardtech. Whether you’re looking for a single contractor, a full-time employee, or an entire team of professionals to work on everything from product development to go-to-market, informal has the perfect collection of people for the job.