On proposal structures: Why T+M rocks and fixed fee sucks

In the world of engineering and design, there are two major categories of how proposals are structured: fixed fee engagements and time and material engagements. Each has their own use cases, advantages and disadvantages, and special flavors. Let’s get into it!

Fixed fee

The first type is called a fixed fee engagement, in which you pay an agreed-upon amount for an agreed-upon deliverable. Fixed fee engagements can be structured in various ways including paying the money upfront, upon delivery, or breaking it into monthly fixed amounts. This type is typically seen as a safe option for clients because the cost is predictable and can be budgeted upfront.

Fixed fee projects work well for very well-defined engagements that have little to no surprises baked into them, and require less effort to create proposals around them. This is why they’re generally the preferred scoping method for creatives. Website redesign work, logo generation, and even some industrial design engagements are great for fixed fee projects. The proposal is typically written to include a handful of concepts, iteration, refinement, and a final design chosen. This work is predictable and easy to estimate.

Time and materials

The other type is a time and materials (T+M) engagement, in which you agree to pay a specific rate for each hour of labor. This type can also be structured in various ways, and typically includes a ceiling of maximum hours paid. Clients may get the heebie-jeebies when presented with a simple hourly rate, so including a maximum hour cap helps to reduce this anxiety.

In my opinion, T+M is the most fair engagement for longer-term, complex, or not fully defined projects where scope creep may occur. If a client wants to meet every day during a project, they’re going to pay for that privilege. If they want more concepts generated, they pay for it. Similarly, if they want to reduce cost, they can be more decisive or move to asynchronous communication. Each hour is valuable.

Monthly cap

A variation of the T+M engagement is a monthly recurring cap, in which a budget of maximum spendable hours resets each month. The client is paying for the ability to tap someone for help, without the fixed price overhead of a retainer or fixed fee engagement. It’s essentially a pay-as-you-go plan for smart folks.

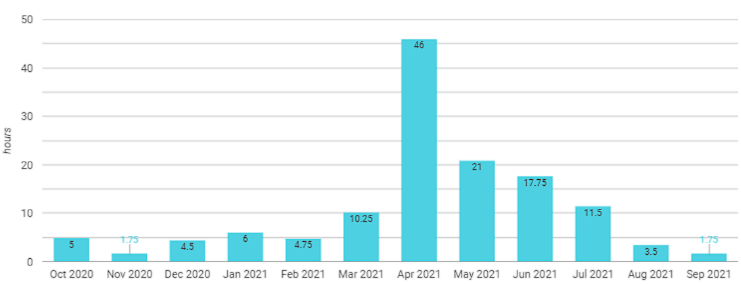

Caps are great for engagements where the workload or priorities may shift, and you’re budgeting a consistent spend for augmenting your team with additional talent. Caps aren’t a great fit for working on new product designs with a full team of engineers and designers, as work happens in fits and starts instead of a consistent burn rate. For example, you may see two to three weeks of intense engineering and design work followed by one to two weeks of silence as prototypes are manufactured and evaluated.

Hours spent by a product design engineer. Notice the spike in April when the industrial design was locked down and it was their turn to work on creating manufacturable prototypes.

A tangent on the term “add value”

A few years ago, someone wrote a book about value-based pricing. (I don’t want to google it to corrupt all the ads I see moving forward.) The idea was that consultants should charge based on the “value” they add to a project instead of a standard rate, regardless of the project. I actually cringe when I hear the term “add value” on calls; it’s gross and predatory, and I think it negatively impacts the entire industry.

Another way to think about value-based pricing is “What is the most amount of money I can charge you for this work?” Imagine going to a restaurant and paying a different price than the person next to you for the same meal because you’re hungrier than them. That’s bonkers, but will probably be a new startup we’ll see in the next year.

If you’re a small company trying to make it in the expensive and fraught world of hardware, every dollar counts. If each firm, agency, and company you work with is trying to milk you for as much cash as possible, you’re going to die before you can launch your product.

Value-based pricing still happens with other project types, but not in an overtly yucky way. For example, we may recommend lowering hourly rates on a long-term engagement since work is more guaranteed. If we’re working with a small company with a mission we strongly believe in, rates may lower. This is more “values-based” pricing.

Why fixed fee projects suck

Choosing the right project type is crucial for structuring an engagement that makes all parties feel valued. This is why I firmly believe that fixed fee projects suck for most engagements.

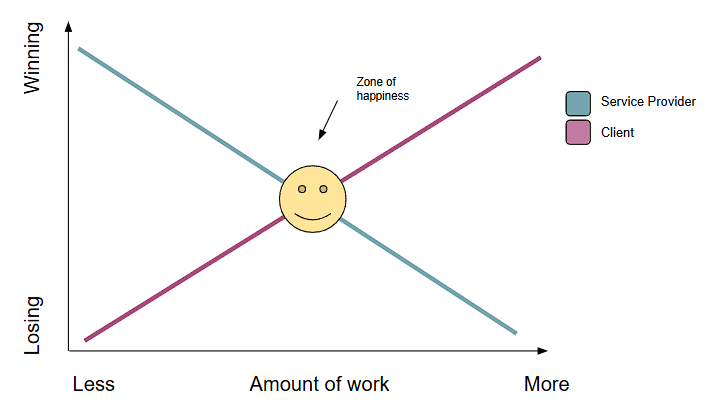

When you boil down any engagement, there’s a quantity of work that is done and a quantity of hours that it took to perform that work. In a fixed fee engagement, each hour of work performed reduces the billable rate for the service provider. Conversely, each of those hours is a cheaper hour of work for the client. Nobody likes being taken advantage of, so there’s tension between the client and the service provider at all times. The service provider is incentivized to work as little as possible to get the job done and maximize their effort-to-profit ratio. The client will want to squeeze out as much work as possible from the service provider in order to get their highest value-to-cost ratio.

There exists exactly one point in time where both sides are feeling jazzed about this engagement — and I call this the zone of happiness. Both parties feel like the amount they make or spend is worth the amount of work that has been done.

The “zone of happiness” in a fixed fee engagement

As more and more work is expected from the service provider, the quality and attention to detail may drop. This project is now a slog and taking up valuable time that could be spent on other engagements.

As a way to hedge against a client potentially trying to eke out as much work as possible, service providers tend to mark up their fixed fee rates to account for additional hours they may need to spend. Now the client is paying more for work that might not happen.

See why this sucks? This is why I think T+M projects are the most honest for all parties involved. Let’s see how we can derisk T+M engagements so all folks feel valued.

How to make T+M projects better

The primary pushback we hear about T+M proposals is that they feel risky to the client. What happens if something takes longer than estimated, or if we need to change the scope? They want predictability, which is absolutely justified.

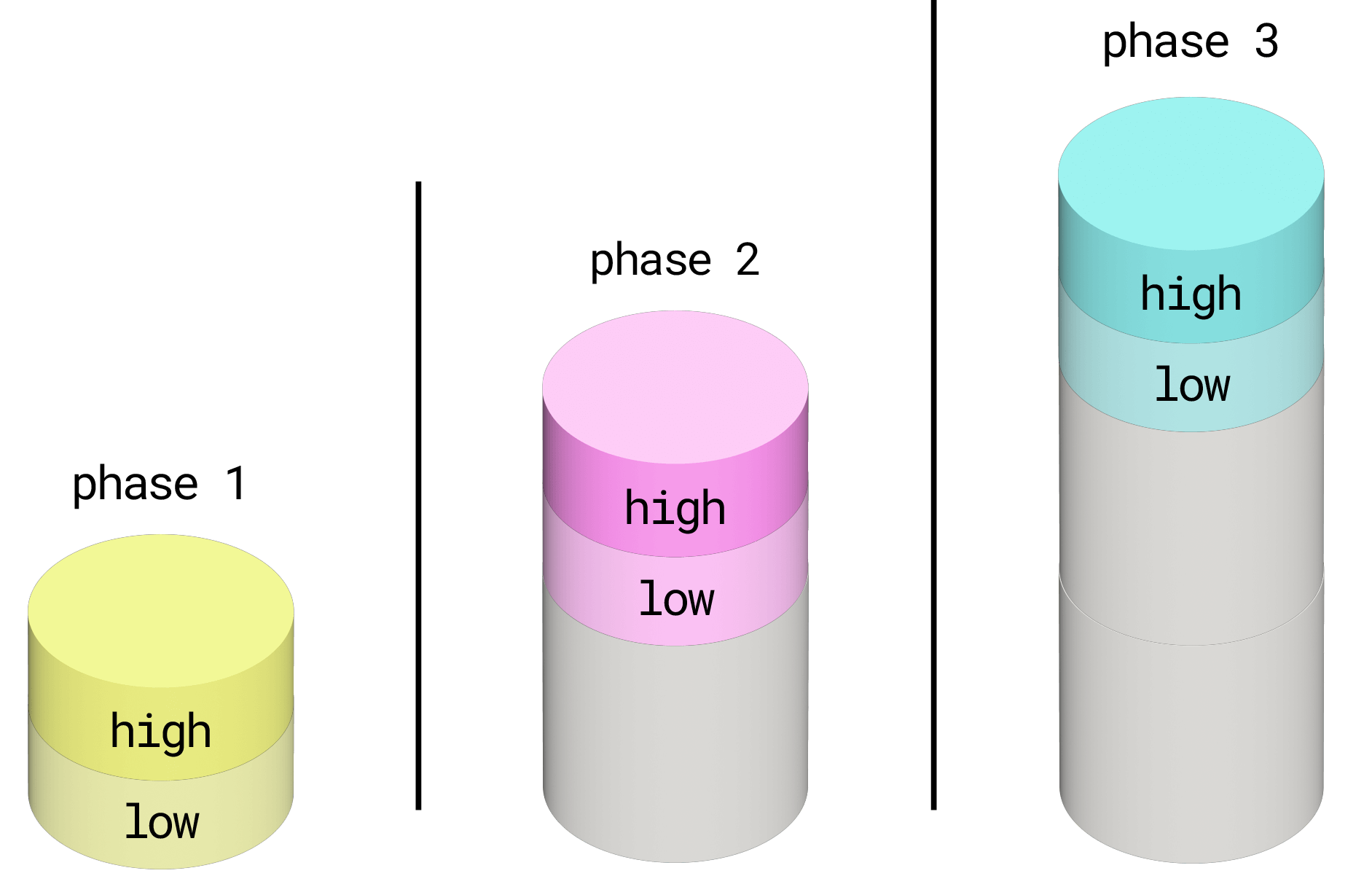

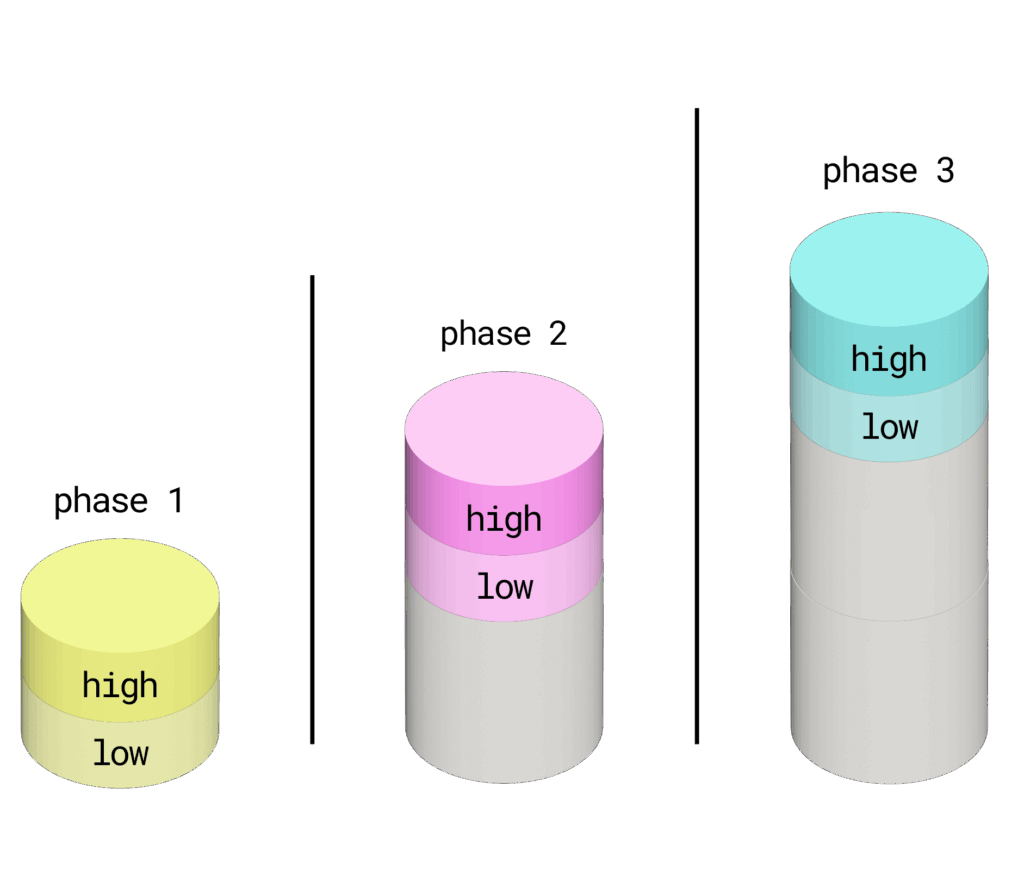

A T+M engagement without an hourly cap is almost as yucky as a fixed fee project. The service provider is basically saying, “It’s gonna cost you, but we can’t tell you how much, so good luck!” Nobody likes this, yet it seems to be how every car mechanic operates. To account for this unpredictability, we modified our T+M proposals to include low and high estimated hours, and we split work into smaller phases.

When quoting an engagement, the first thing we do is make sure we feel confident we can accurately estimate the hours. For something simple like “given this industrial design concept, create a manufacturable plastic enclosure,” this can usually be accurately estimated. For something more heady like “take my 3D-printed Arduino prototype and mass manufacture 10,000 units,” we’re going to do a bad job at estimating because there are too many unknowns.

In a situation like this, we chop up our project into smaller phases of work. Phase 1 may be a discovery session where we review the current prototype and create a block diagram and system architecture for moving to something more mass-manufacturing friendly than an Arduino. After this work is completed, we have a much better understanding of the work needed to create a prototype using these components and meeting the specifications we defined in Phase 1. After we make a prototype, we’ll have a much better understanding of what it’ll take to make a mass-manufacturable enclosure. Baby steps! I liken this to “fog of war” in the videogame Age of Empires (nerd). We don’t know what lies ahead, and the only way to know is to explore it.

Engineers get analysis paralysis quickly, so breaking work into phases makes sure each quote is accurate and has the least amount of uncertainty involved. A common pushback on this phase-based approach is that a company wants to see a total project cost for budgetary purposes. I get the need, but it’s a bit like asking me, “How much does it cost to build a house?” I can’t give you a cost unless I know what I’m building. For these cases, I recommend we provide an accurate phase 1 quote, and some SWAG (scientific wild-ass guess) estimates for future phases — with the caveat that we’ll requote at the end of each phase. This is a nice balance of accurate guesses and inaccurate guesses that seems to please both parties well.

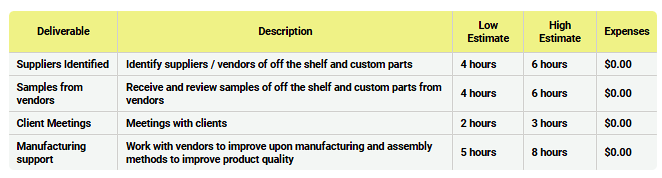

The other thing we’ve implemented to improve the T+M quoting process is to provide detailed estimates on deliverables with a low and high hourly range. Instead of receiving a proposal that says “I’ll need 240 hours to do this,” the client receives a table like this:

Our freelancers are provided a quotation tool that asks them how few hours they think a deliverable may take if all goes well and how many it may take in a worst case scenario. Our proposals ask for permission to bill for the higher estimate, but show a potential range of hours to expect. There is goopiness involved in hardware, and things can take more or less time. We’ve received positive feedback from clients and freelancers that this method is less intimidating for both parties involved.

Quoting smaller, easier-to-predict phases of work with our low and high hour estimates allows us to provide more accurate estimates that value the freelancer’s time and the client’s budget simultaneously.

Wanna see how this works in real life? Hit me up and we’ll get a proposal going for your hardware project!

informal is a freelance collective for the most talented independent professionals in hardware and hardtech. Whether you’re looking for a single contractor, a full-time employee, or an entire team of professionals to work on everything from product development to go-to-market, informal has the perfect collection of people for the job.