Evolved structures and generative design for DIY

Image courtesy of Autodesk

I’ve heard some people describe AI as a brainstorming partner, a “wall” you can throw spaghetti at that won’t start to smell after a while — or judge you for your bad ideas. I didn’t quite understand how to effectively use AI as a partner. My corners of the internet were more interested in what the use of AI meant for art, and either decried anything even mentioning the technology as theft, or wholeheartedly welcomed the death of artists and their “gatekeeping.” The idea of a computerized thought partner didn’t fully crystallize until I began looking more deeply into Ryan McClelland of NASA’s “evolved structures.”

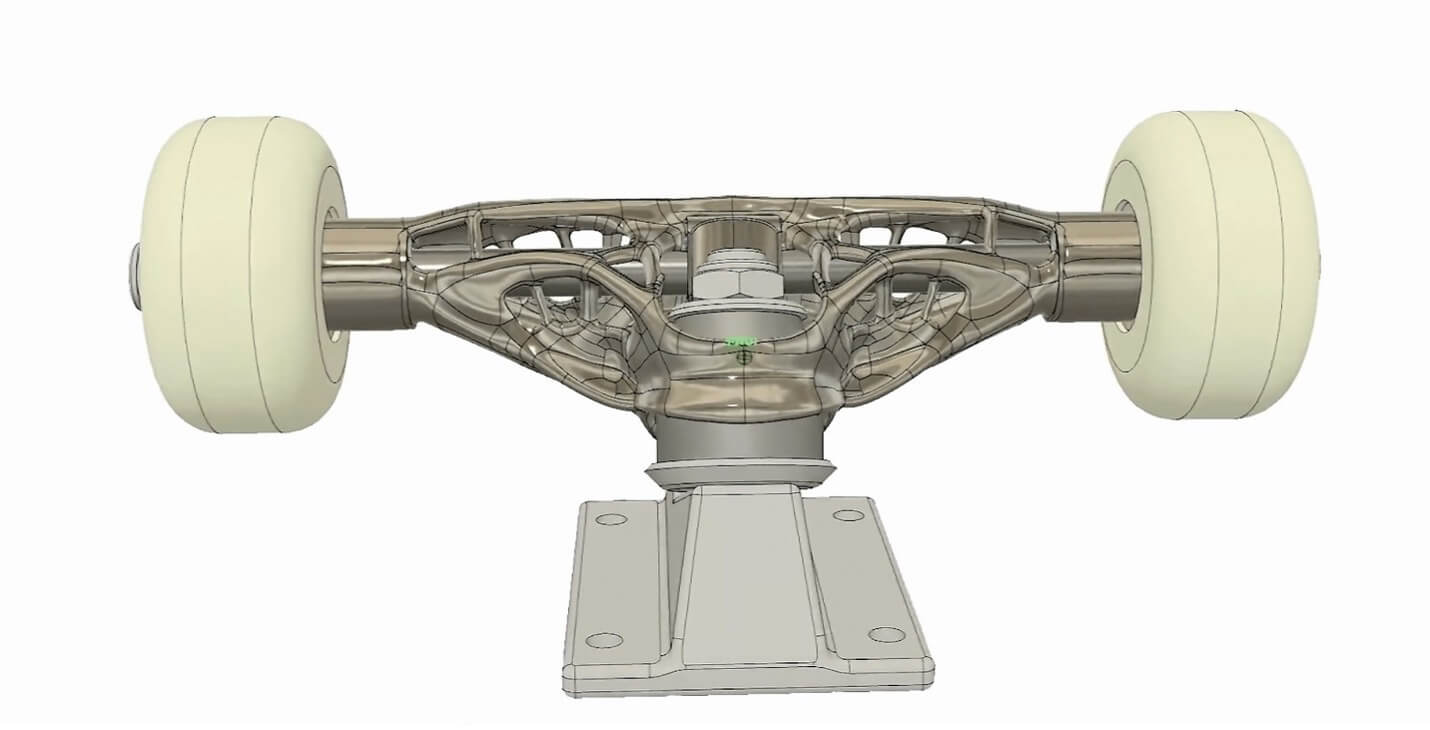

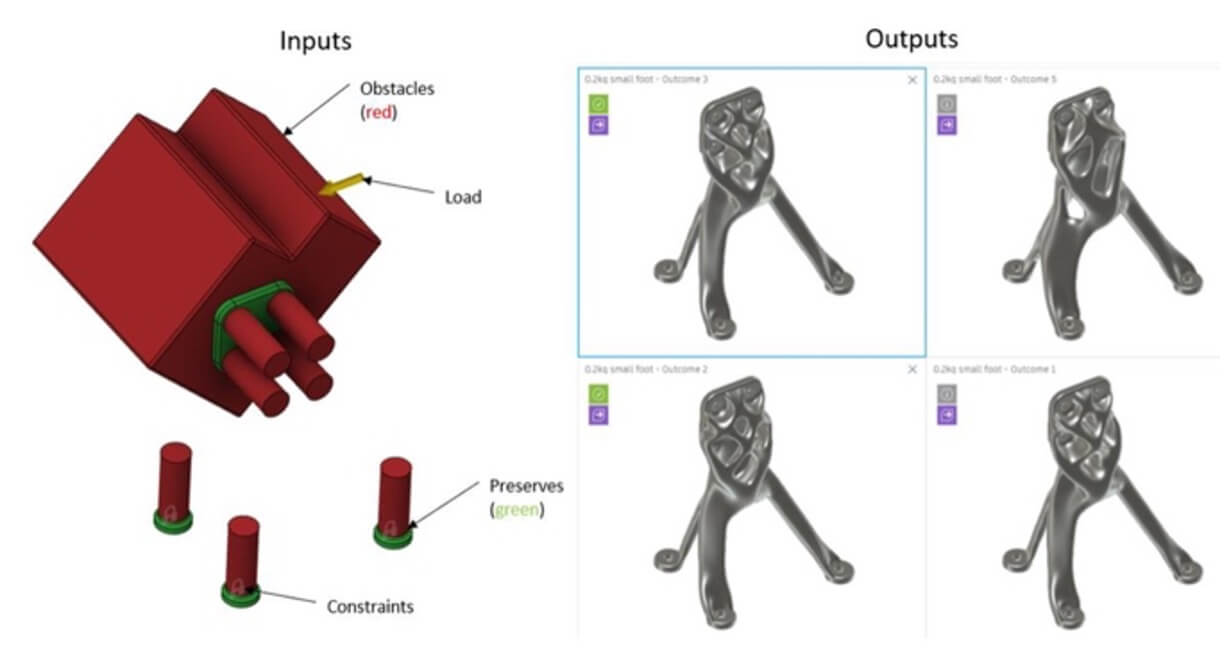

Recently, NASA engineer Ryan McClelland made headlines with his evolved structures bespoke parts for NASA expeditions, which resemble something an alien might have crash-landed. They’re quite beautiful, twisting and turning in a way that feels familiar but also strange. They’re almost too perfect, too exact. The structures are made by providing detailed engineering requirements to an algorithm, then having that algorithm iterate through a plethora of possible solutions. One solution is then manually chosen by an engineer, who runs simulations to ensure it’ll perform as expected, and that it can be manufactured using available equipment.

Image courtesy of NASA

The perfect use case for AI assumes human participation

In interviews and statements, McClelland often refers to the need to ensure the algorithm is being provided with exacting data. Garbage in, garbage out — even more so when working with a machine that can’t intuit what you meant to say. The AI can only work with the information it’s given. Likewise, an engineer likely wouldn’t have come to some of the wild solutions the computer entertains, and certainly not in the same amount of time. Then, the human mind comes in again — determining what “feels right” and which structures look sturdy enough.

McClelland posits that this type of check is the same type many of us did as children — for example, that tree branch doesn’t look like it could support my weight. I’m not walking across that log; it looks like it’ll break and take me with it. The most surprising and interesting aspect of these alien structures is this “check” that asks us to lean more into our humanity and make decisions based on feeling.

I’m curious to see how this vibes-based decision-making develops in conjunction with our use of AI. Will we lean into the unknowable and unnamable variables that comprise human decision-making? Or will we try to engineer it out, and put names and numbers to what has, for centuries, just amounted to a gut feeling?

From where I’m standing, this seems like the perfect use-case for the AI we have now. Humans define the guardrails present in the real world, the desired outcome, and turn it over to the machine. Then, humans come in again to weigh the machine’s outputs against their intuition to select the solution that will work best. The human isn’t replaced, they’re augmented.

Image courtesy of Autodesk

How to get started with this model of AI

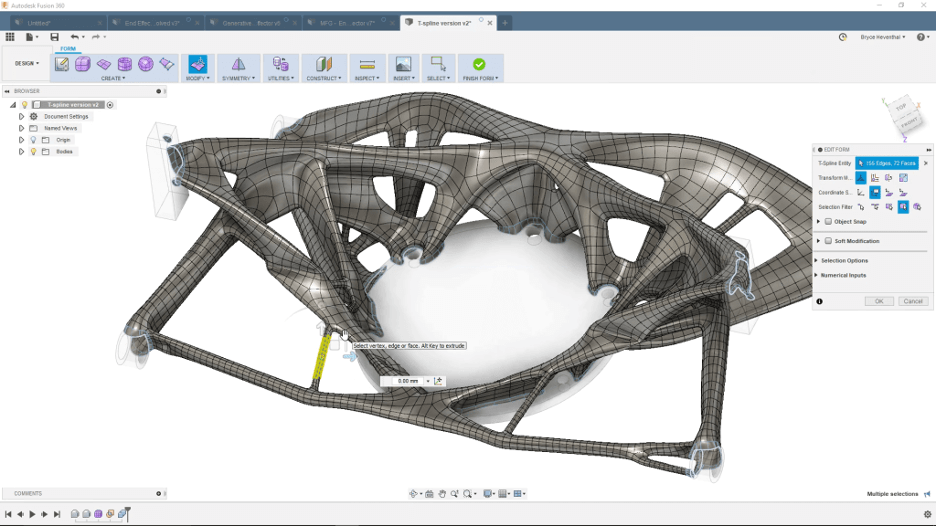

By this point in my research, I was curious as to how one goes about using this technology. There’s a wealth of information about image generation and text prompts for ChatGPT, but generative design doesn’t seem to have captured the imagination of the DIY crowd in the same way — yet.

Currently, this software is used in a B2B/industrial fashion, by giant companies doing complex, bespoke processes for other giant companies: engines that need to fit into a specified size hole in a chassis and have a predetermined displacement, aerospace parts that need to withstand specific stresses and hold exacting amounts of weight. But where are the toys? Why can’t individual and small-time entrepreneurs use this technology to create consumer electronics or accessories that look like they were imagined, manufactured on Mars?

At first shake, it seems like overengineering — do we really need to come up with 30 iterations of a doorbell or water bottle? No, of course we don’t. But what might happen if we did? Could we create a water bottle that never tips over, but also weighs less than a pound when empty? Could generative design offer out-of-the-box, never-before-imagined ideas to reduce the weight and consequently the shipping costs of our products? More efficiency also means less emissions as we ship our needs and wants from one side of the globe to another. This type of overengineering could help our warming planet — and look amazing and futuristic while doing so.

In my research, Fusion 360 came up as being a good option for those interested in generative design to get started especially if you’re already in the Autodesk ecosystem. However, it isn’t cheap ($1600) and there are other options that one could consider.

Rather than spending our energy debating whether AI art is legit, I hope we’ll all consider how generative design can help us create our own evolved structures. Right now, the best time and place for this tech isn’t when we have something to say — it’s when we have something to make.